auslistings.org

A well-established growth hub for Australian businesses

★ Get your own unique FAQ + Selling Points on your profile page

★ be seen by 1000s of daily visitors and win new business

auslistings.org Ephemeral Miniblog

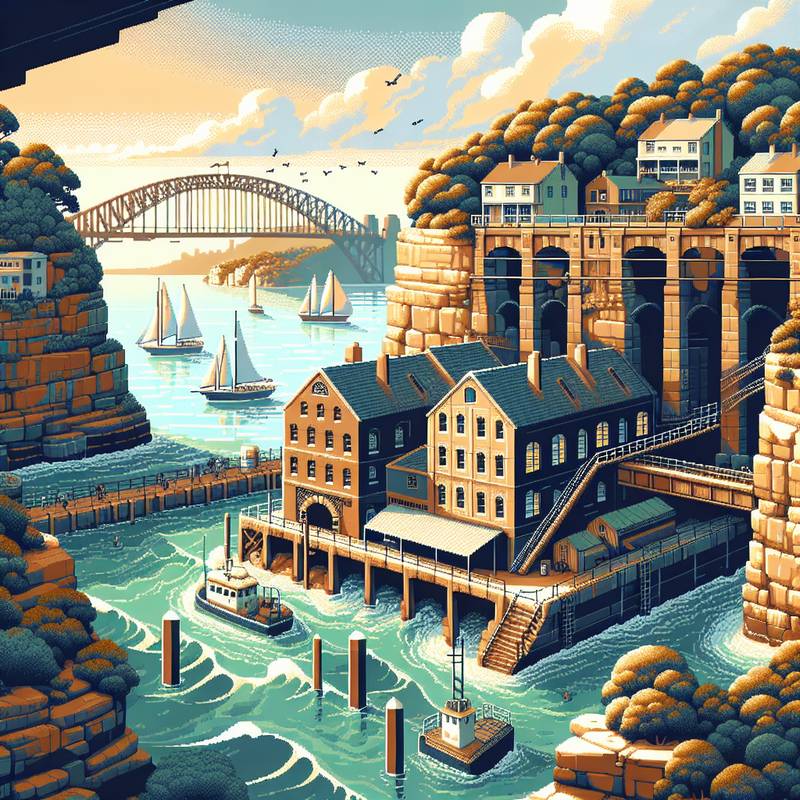

Beneath McMahons Point

If you walk along the edge of Sydney Harbour, past the post-card views and curated tourist gloss, you’ll find McMahons Point. It’s quiet there—residential, unassuming. There’s a coal loader—yes, still—and a stretch of green where trees lean in close. But the real secret rests beneath your feet. Old, forgotten tunnels from World War II, dug into the sandstone, built for storage, for war, for defense. Locals know they’re there. Some grew up daring each other to slip behind rusted gates, flashlights in hand. The air down there carries the damp weight of history, must and echoes. It’s easy to walk above and think the world is all surface, sun and ferry wakes. But this place remembers a different time, and it’s not interested in being glamorous. It’s a reminder that even the brightest places hold shadows. There’s a hollow quiet here that speaks louder than any tour guide ever could. Locals don’t make a fuss—they just nod toward the past and keep walking.

If you walk along the edge of Sydney Harbour, past the post-card views and curated tourist gloss, you’ll find McMahons Point. It’s quiet there—residential, unassuming. There’s a coal loader—yes, still—and a stretch of green where trees lean in close. But the real secret rests beneath your feet. Old, forgotten tunnels from World War II, dug into the sandstone, built for storage, for war, for defense. Locals know they’re there. Some grew up daring each other to slip behind rusted gates, flashlights in hand. The air down there carries the damp weight of history, must and echoes. It’s easy to walk above and think the world is all surface, sun and ferry wakes. But this place remembers a different time, and it’s not interested in being glamorous. It’s a reminder that even the brightest places hold shadows. There’s a hollow quiet here that speaks louder than any tour guide ever could. Locals don’t make a fuss—they just nod toward the past and keep walking.Loading...

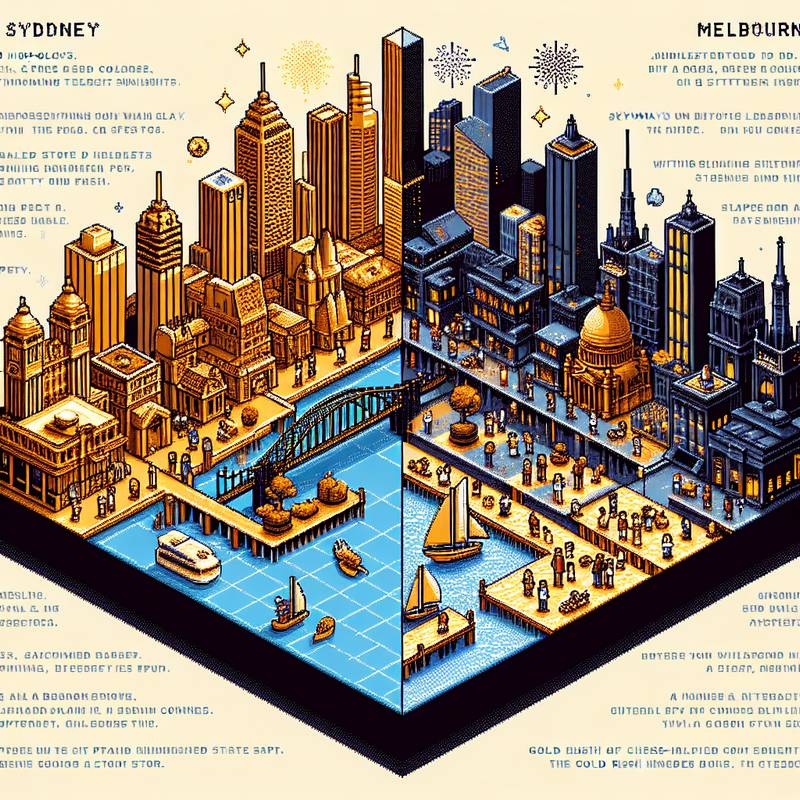

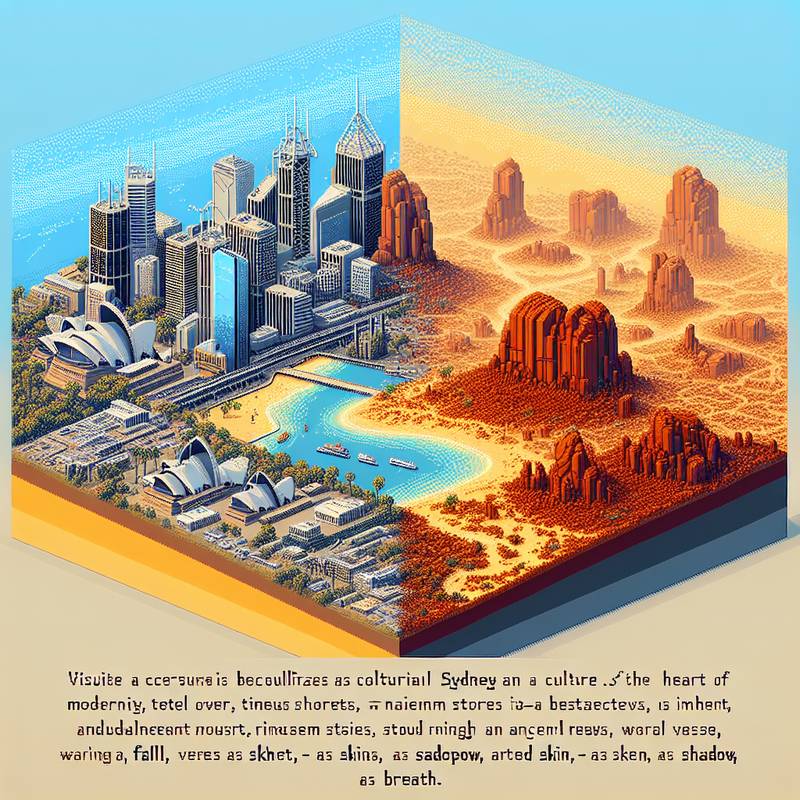

The Two Faces of a Southern Continent

Sydney, with its high-gloss harbor and steel-ribbed bridge, feels like a city always mid-stride—well-dressed, coffee in hand, talking fast. Its heart beats to tides lapping against sandstone coves, skyline chasing sunlight. Melbourne, though, lounges with quiet poise. Laneways whisper of literary secrets and jazz spilled over from basement corners; it’s a city that reads before it speaks.

Sydney, with its high-gloss harbor and steel-ribbed bridge, feels like a city always mid-stride—well-dressed, coffee in hand, talking fast. Its heart beats to tides lapping against sandstone coves, skyline chasing sunlight. Melbourne, though, lounges with quiet poise. Laneways whisper of literary secrets and jazz spilled over from basement corners; it’s a city that reads before it speaks.Culturally, Sydney hosts spectacle—opera beneath sails, fireworks like brushstrokes across the sky. Melbourne curates intimacy: a poetry reading above a record store, footy fandom with tribal devotion. Both cities reach for identity, one outward and bright, the other inward, coal-warmed and curled like smoke.

Historically, Sydney wears its convict past like a pressed uniform, cleaned but not discarded. In contrast, Melbourne’s gold rush roots shimmer not only in museum display but in a subconscious glint in its architecture—regal façades built to impress, and still trying.

Geographically, Sydney tumbles across headlands and into sea, a vista city. Melbourne spreads with purpose, its streets a chessboard. The difference is tone: Sydney sings in soprano; Melbourne speaks in mellow baritone.

Loading...

The Note That Sang

If you only know one thing about Dame Nellie Melba, it should be that she conquered the world’s grandest stages while still hearing the magpies of Melbourne in her dreams. Born Helen Porter Mitchell, she slipped into a pseudonym like a silk glove – “Melba” for her beloved city – and sang her way into immortality. Her voice was the sort that makes cathedrals seem inadequate and silence feel full. She was no mere soprano; she was a living crescendo, a nightingale dipped in velvet.

If you only know one thing about Dame Nellie Melba, it should be that she conquered the world’s grandest stages while still hearing the magpies of Melbourne in her dreams. Born Helen Porter Mitchell, she slipped into a pseudonym like a silk glove – “Melba” for her beloved city – and sang her way into immortality. Her voice was the sort that makes cathedrals seem inadequate and silence feel full. She was no mere soprano; she was a living crescendo, a nightingale dipped in velvet.At Covent Garden, they adored her. At the Metropolitan Opera, they worshipped. Yet she returned often to the eucalyptus-scented air of Australia, like a diva homesick for sunlight. She didn’t just perform, she redefined what it meant to be Australian on the global stage: not rough and ready, but radiant and refined.

Melba’s portrait now graces the hundred-dollar note not because of her fame, but because she transformed art into something unforgettably human—even when that human was extraordinary.

Loading...

The Eerie Allure of The Pilliga Scrub

The Pilliga Scrub—charmingly named like a cough medicine but closer in spirit to a gothic novella set in a eucalyptus-suffocated wilderness—is the largest native forest west of the Great Dividing Range. Stretching across New South Wales like nature's overgrown middle finger to urban sprawl, it's part labyrinth, part time capsule, part hallucinogenic fever dream.

The Pilliga Scrub—charmingly named like a cough medicine but closer in spirit to a gothic novella set in a eucalyptus-suffocated wilderness—is the largest native forest west of the Great Dividing Range. Stretching across New South Wales like nature's overgrown middle finger to urban sprawl, it's part labyrinth, part time capsule, part hallucinogenic fever dream. Forget sanitised national parks with gift shops flogging $12 magnets shaped like kangaroos. The Pilliga offers over 5,000 square kilometres of twisted trees, sandstone caves, and inexplicable sculptures carved by some bloke in the 1970s who clearly had issues with reality. And that’s its charm. This isn’t nature curated—it’s nature unmedicated. There are ghost gums, emus acting like they’ve had one too many energy drinks, and a palpable sense that you could vanish without trace and nobody would mind. Which, depending on your worldview, is either terrifying or liberating.

It’s not easy, it’s not glossy, and it doesn’t fit on an Instagram square. But it’s real—and increasingly, that counts for something.

Loading...

Woomik

A hundred years ago in the mallee scrub, where the wind moves like a scavenger through saltbush and sand, folk spoke of a thing as being “woomik.” Not broken, not ruined, not useless—simply not what it once was. A tool weathered soft, a fence leaning into the earth, a dog no longer keen to chase: woomik. The word has nearly vanished now, but it fit a world that knew the slow erosion of usefulness.

A hundred years ago in the mallee scrub, where the wind moves like a scavenger through saltbush and sand, folk spoke of a thing as being “woomik.” Not broken, not ruined, not useless—simply not what it once was. A tool weathered soft, a fence leaning into the earth, a dog no longer keen to chase: woomik. The word has nearly vanished now, but it fit a world that knew the slow erosion of usefulness.Such language carries a kind of mercy. In calling something woomik, there’s no contempt, only recognition of change. It presumes a lifecycle not just for living things, but for tools, structures, intentions. It signals an acceptance of time’s passage, and a refusal to demand perpetual utility.

To lose a word like this is to lose a way of seeing. Cultures that endure on the edges—among drought, dust, and distance—learn to live with the worn and fading. They need names for those things. And they carry them like flint in the pocket, even if the fire’s not needed yet.

Loading...

The Man, The Myth, The Pool

If you only know one thing about Harold Holt, it’s that Australia named a swimming pool after the prime minister who vanished while... swimming. Yes. The Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre. You can’t make this up. It’s kind of like building a treehouse in honor of Newton’s apple-related head injury. Holt disappeared off the coast of Victoria in 1967, and while there are endless conspiracy theories — submarines, desertion, sea monsters with a flair for irony — the most likely scenario is the sea just did sea things. Still, the whole situation is like Australia looked tragedy in the eye and said, “We process with facilities.” It’s both a tribute and a national inside joke, wrapped in a chlorinated enigma. The best part? People go there to relax. Leisure. Laps. Legacy. It's a uniquely Australian blend of reverence, resilience, and a dash of surreal, which kind of says everything about how the country handles its folklore.

If you only know one thing about Harold Holt, it’s that Australia named a swimming pool after the prime minister who vanished while... swimming. Yes. The Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre. You can’t make this up. It’s kind of like building a treehouse in honor of Newton’s apple-related head injury. Holt disappeared off the coast of Victoria in 1967, and while there are endless conspiracy theories — submarines, desertion, sea monsters with a flair for irony — the most likely scenario is the sea just did sea things. Still, the whole situation is like Australia looked tragedy in the eye and said, “We process with facilities.” It’s both a tribute and a national inside joke, wrapped in a chlorinated enigma. The best part? People go there to relax. Leisure. Laps. Legacy. It's a uniquely Australian blend of reverence, resilience, and a dash of surreal, which kind of says everything about how the country handles its folklore.Loading...

Ghosts in the Quartz

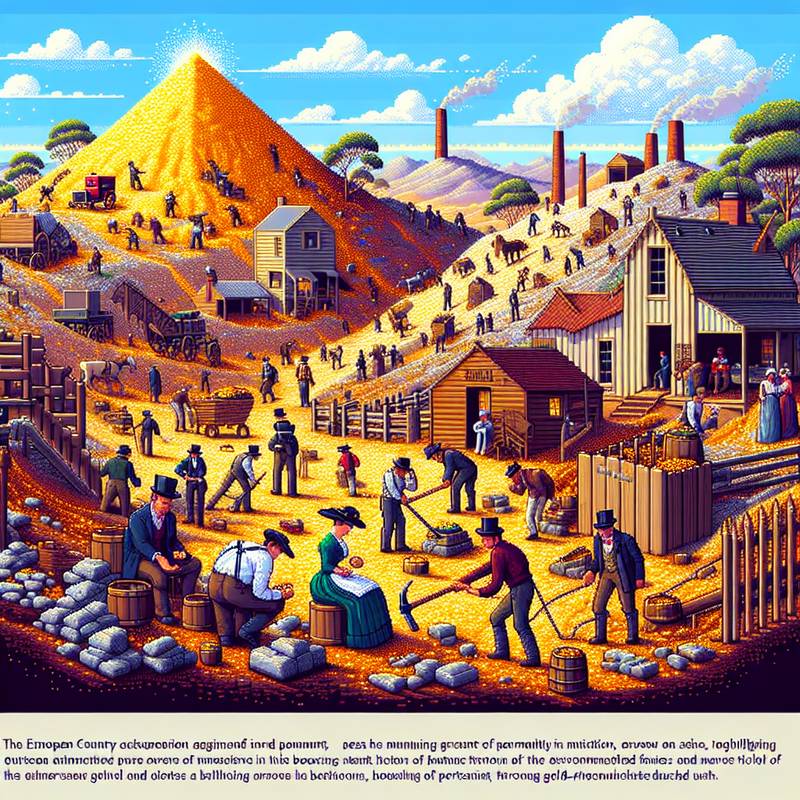

The air is thick with ash and eucalyptus oil. It's 1851, and gold is breaking through the soil like some fever dream. Thousands pour in, their hopes as gaudy as their waistcoats. They come to Ballarat, Bendigo, seeking redemption or ruin—either will do. Tents bloom in the dust, shanty towns buzz with ambition, and the land, once ancient and quiet, cracks open under picks and desperation.

The air is thick with ash and eucalyptus oil. It's 1851, and gold is breaking through the soil like some fever dream. Thousands pour in, their hopes as gaudy as their waistcoats. They come to Ballarat, Bendigo, seeking redemption or ruin—either will do. Tents bloom in the dust, shanty towns buzz with ambition, and the land, once ancient and quiet, cracks open under picks and desperation.By the 1860s, the veins run deep. Cities swell. Wealth licks the edges of civility, curls into art galleries and marble arcades. It’s beautiful from far away—whiskey reflections off gilded mirrors, the right gloss of progress. But underneath, always that howling: dispossession, the bones beneath the boom.

Then the decline. The glitter fades to inertia. Still, the myth survives. We romanticize the rush, the sweat, the rawness of it all. It’s cleaner that way. We pretend the gold just appeared, not torn from the earth, not drowned in blood and smoke.

Because that story feels good. And we like our stories gold-plated, even when they’re rusting underneath.

Loading...

If You Only Know One Thing About Kakadu National Park

If you only know one thing about Kakadu National Park, let it be this: it’s not just a park, it’s 20,000 square kilometers of otherworldly wonder where the land literally tells stories older than the pyramids. I’m talking Aboriginal rock art so ancient, it makes Instagram filters look like cave scribbles. Some of the paintings found in Ubirr and Nourlangie are believed to be 20,000 years old—yes, with four zeros—and they’re still vibrant, still fierce, still telling Dreamtime stories passed down through generations of the Bininj and Mungguy people. Walking through Kakadu is like stepping into a gallery curated by the oldest continuous culture on Earth. Plus, there are crocodiles with more confidence than most celebrities, waterfalls that deserve their own fragrance line, and wetlands that make you reevaluate all your life choices (why don’t I live here again?). So while people might romanticize the Eiffel Tower or the Grand Canyon, Kakadu is quietly out here being the Beyoncé of natural wonders: iconic, timeless, and absolutely not overrated.

If you only know one thing about Kakadu National Park, let it be this: it’s not just a park, it’s 20,000 square kilometers of otherworldly wonder where the land literally tells stories older than the pyramids. I’m talking Aboriginal rock art so ancient, it makes Instagram filters look like cave scribbles. Some of the paintings found in Ubirr and Nourlangie are believed to be 20,000 years old—yes, with four zeros—and they’re still vibrant, still fierce, still telling Dreamtime stories passed down through generations of the Bininj and Mungguy people. Walking through Kakadu is like stepping into a gallery curated by the oldest continuous culture on Earth. Plus, there are crocodiles with more confidence than most celebrities, waterfalls that deserve their own fragrance line, and wetlands that make you reevaluate all your life choices (why don’t I live here again?). So while people might romanticize the Eiffel Tower or the Grand Canyon, Kakadu is quietly out here being the Beyoncé of natural wonders: iconic, timeless, and absolutely not overrated.Loading...

Bushranger’s Breakfast

In the drought-bitten heart of the bush, when the wheat failed and the children’s cheeks turned hollow, there was a word like worn leather: bushranger’s breakfast. It meant a meal of nothing—just a sniff of morning air. No bread. No tea. Just the rising sun and the ache of endurance filling your gut. Not a joke. A truth.

In the drought-bitten heart of the bush, when the wheat failed and the children’s cheeks turned hollow, there was a word like worn leather: bushranger’s breakfast. It meant a meal of nothing—just a sniff of morning air. No bread. No tea. Just the rising sun and the ache of endurance filling your gut. Not a joke. A truth.Language in the outback does not waste breath. It names struggle with grim clarity. Bushranger’s breakfast is not mere slang—it is cultural marrow, born of dry seasons, colonial dislocation, and the inherited silence of dispossession. One phrase, half a joke, half a wound, carries the memory of survival without ceremony.

Such words cluster in the corners of language, where the polite and comfortable won't look. But they thrum like blood vessels beneath the surface, speaking of hunger, pride, and the raw edges of place. They remind us that storytelling isn’t always song—it can also be the sound of a belly echoing the red emptiness of the land.

Loading...

Banjo Paterson and the Poetry of a Nation

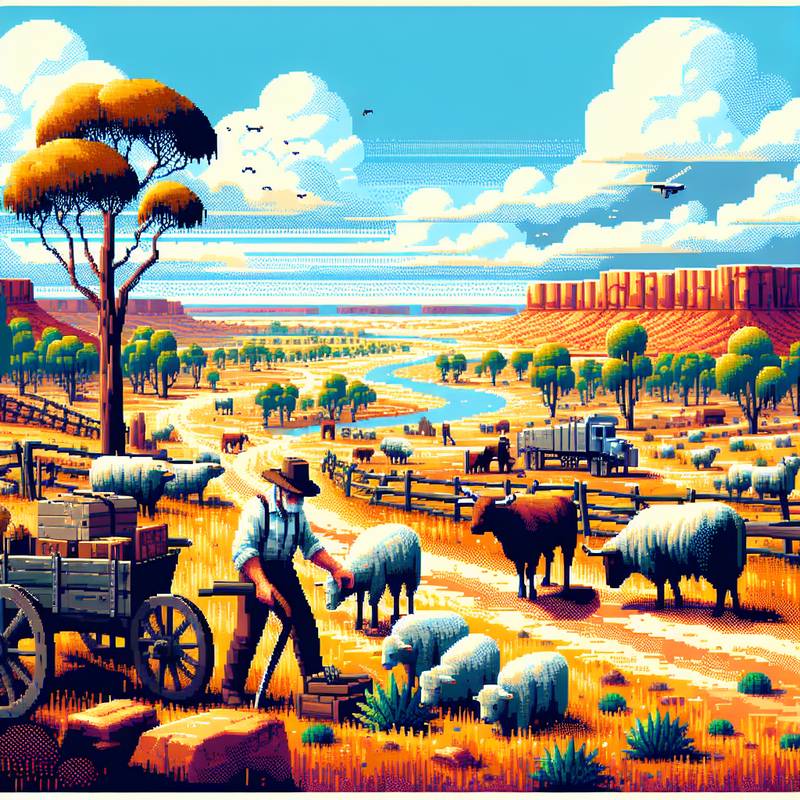

If you only know one thing about Banjo Paterson, let it be this: he lent Australia a voice that sang not merely of landscape but of character, and in doing so, he fixed the bushman to the nation’s soul. With the easy gait of a stockman and a pen dipped in the ink of sympathy, humour, and quiet pride, Mr Paterson chronicled the spirit of the frontier with an elegance that belied its ruggedness. His verse did not condescend to the toiling drover or the laconic shearer; rather, it elevated them, rendering their hardships and heroics with a clarity that honoured both truth and legend. Where others saw only distance and dust, he saw dignity.

If you only know one thing about Banjo Paterson, let it be this: he lent Australia a voice that sang not merely of landscape but of character, and in doing so, he fixed the bushman to the nation’s soul. With the easy gait of a stockman and a pen dipped in the ink of sympathy, humour, and quiet pride, Mr Paterson chronicled the spirit of the frontier with an elegance that belied its ruggedness. His verse did not condescend to the toiling drover or the laconic shearer; rather, it elevated them, rendering their hardships and heroics with a clarity that honoured both truth and legend. Where others saw only distance and dust, he saw dignity. Through works such as The Man from Snowy River and Waltzing Matilda, he did not merely write of a life—he rendered a mythology, one in which mateship and resilience are virtues, where the horizon is never just a line, but a promise. That is the essence of Banjo Paterson’s gift: he made the Australian heart legible to itself.

Loading...

The Underground World of Coober Pedy

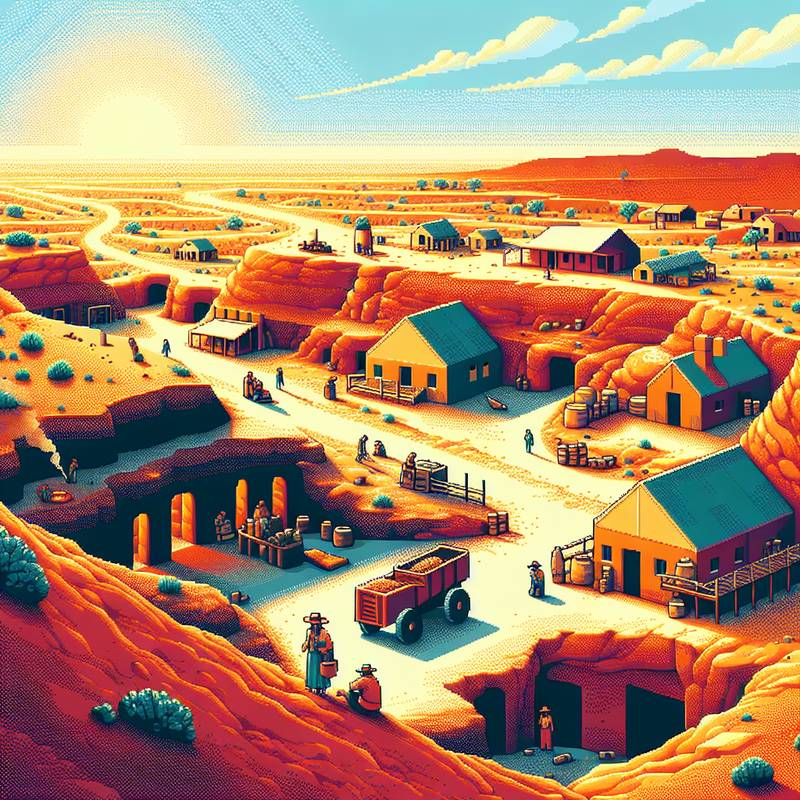

If you only know one thing about the town of Coober Pedy, it must be this: its people reside beneath the earth not out of whimsy, but necessity. Situated in South Australia’s blistering interior, where the sun reigns with relentless ardour, inhabitants have long since retired from the surface world, fashioning elegant abodes within the ancient sandstone. These subterranean dwellings, called “dugouts,” offer a respite from heat that often exceeds forty degrees Celsius.

If you only know one thing about the town of Coober Pedy, it must be this: its people reside beneath the earth not out of whimsy, but necessity. Situated in South Australia’s blistering interior, where the sun reigns with relentless ardour, inhabitants have long since retired from the surface world, fashioning elegant abodes within the ancient sandstone. These subterranean dwellings, called “dugouts,” offer a respite from heat that often exceeds forty degrees Celsius. Yet Coober Pedy is not merely a marvel of adaptation; it is the opal capital of the globe, a place where fortune is wrested from below with both reverence and toil. Men and women, driven by equal parts enterprise and endurance, have for over a century braved the desert's severity in pursuit of those radiant stones that catch the light like bottled lightning. In Coober Pedy, one does not merely survive; one flourishes, concealed artfully beneath a parched and shimmering crust.

Loading...

16 January: The Day Australia Outsurrealled Itself

On this day (16 January), Australia continued its long-standing tradition of being the world’s premiere destination for both natural beauty and absolute chaos. In 1967, Harold Holt, the prime minister who apparently fancied himself as a human torpedo, was officially declared dead after vanishing into the surf a month earlier. Nothing like starting the year with your head of state evaporating into the ocean like a political sea monkey.

On this day (16 January), Australia continued its long-standing tradition of being the world’s premiere destination for both natural beauty and absolute chaos. In 1967, Harold Holt, the prime minister who apparently fancied himself as a human torpedo, was officially declared dead after vanishing into the surf a month earlier. Nothing like starting the year with your head of state evaporating into the ocean like a political sea monkey.Then there’s the 1939 Black Friday bushfires in Victoria—because Australia doesn’t do forest fires, it does biblical vengeance. Nearly 5 million hectares burned, with temperatures so high you’d have thought Satan himself had popped down to toast a marshmallow on the Opera House.

On a lighter note, tennis legend Lleyton Hewitt was born in Adelaide in 1981. A man whose competitiveness made even seagulls nervous. He went on to become the youngest male ever ranked world No. 1—because nothing motivates an Aussie teen quite like the thought of yelling 'C’MON!' at strangers in shorts.

Loading...

How Australia Found Its Glimmer

The gold came like a rumor, then a fever. In 1851, men with empty hands and wide eyes clawed at the ground near Bathurst. A whisper turned into a migration. They brought shovels and hopes the size of small continents. The hills glittered. Towns puffed up overnight — shanties, saloons, and the sound of accents arriving from every corner of the globe, colliding into something like a country.

The gold came like a rumor, then a fever. In 1851, men with empty hands and wide eyes clawed at the ground near Bathurst. A whisper turned into a migration. They brought shovels and hopes the size of small continents. The hills glittered. Towns puffed up overnight — shanties, saloons, and the sound of accents arriving from every corner of the globe, colliding into something like a country.Soon, the ground was pockmarked and hungover with holes. The European dream of permanence—stone fences, tea at four o'clock—found itself lunging into the dust of this sudden gold-drenched rush.

It was not just about gold. It was about arrival, and how the thing you come for is never quite the thing you find. A young country, half-formed and already shaken, looked into the mirror of greed and saw its first glint of self. In the end, the gold ran out, or deeper in, and many stayed, waiting for another miracle or just too tired to leave.

Loading...

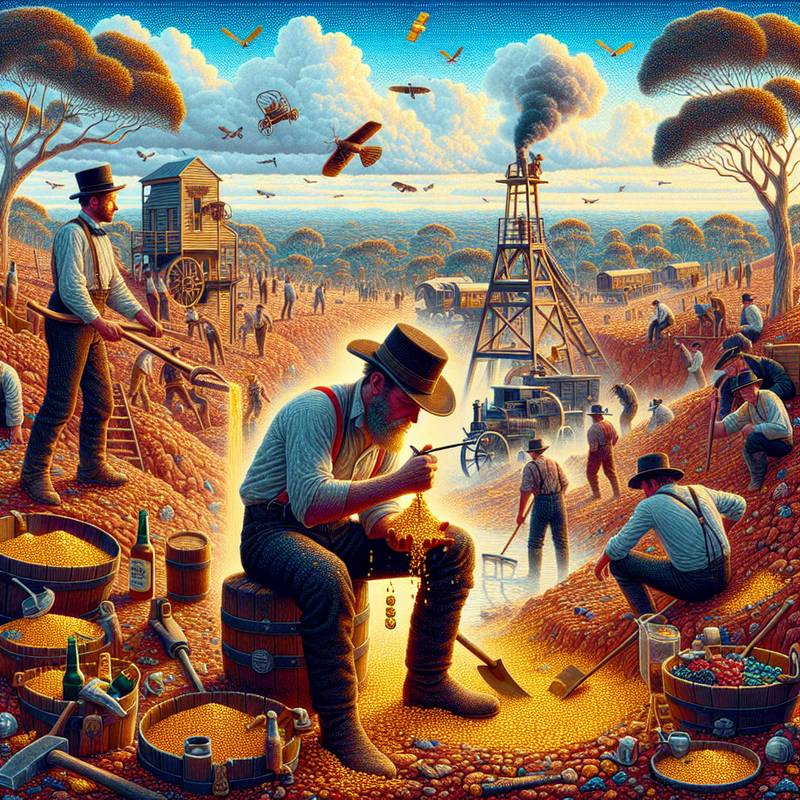

Gold Fever: A Compressed History of the Australian Gold Rush

The sun had that bleached, overexposed quality again. No clouds, just heat humming off the highway. 1851, Bendigo. Dust, fever, gold in the gums of the earth. Men—some too young, most too desperate—dug, fought, drank, dreamed. Ten years later, they’d carved towns from nothing, built mythologies from quartz veins, and died just as quickly.

The sun had that bleached, overexposed quality again. No clouds, just heat humming off the highway. 1851, Bendigo. Dust, fever, gold in the gums of the earth. Men—some too young, most too desperate—dug, fought, drank, dreamed. Ten years later, they’d carved towns from nothing, built mythologies from quartz veins, and died just as quickly.By the '70s, the gold boom had slowed but the damage and the legend remained—rusted tools half-buried in reddened soil, stories passed like currency in pubs with sticky floors. Kids in uniforms still learn about Eureka, but no one tells them about the eyes of a man who’s lost eight pints of sweat for one glint in a pan, or the silence of a shaft closing over a broken back.

Now, in Melbourne’s sterile galleries and curated walks, gold is luxury again. The story’s polished. They don’t mention how the land was never theirs to dig or how greed smelled like kerosene and vomit. It was a rush, sure. A fever. And it burned through everything it touched.

Loading...

The 13th Down Under: Heatwaves, Bridges, and Beach Boys

On this day (13 January), Australia experienced a few moments that make you wonder if the calendar sometimes has a sense of humor.

On this day (13 January), Australia experienced a few moments that make you wonder if the calendar sometimes has a sense of humor.In 1939, Melbourne recorded its hottest day ever at the time—45.6°C. That’s not weather, that’s a dare. It’s like the sun looked down and said, “What if we cook the air?” Meanwhile, the average Australian response was probably, “Yeah, but it’s a dry heat.”

Then in 1941, Australia’s longest suspension bridge—the iconic Story Bridge in Brisbane—opened. A structure that lets cars float over water while being suspended in mid-air. That's basically magic with an engineering degree.

And in 1965, the surf rock band The Beach Boys landed in Sydney. That's right—the Beach Boys in a country where beaches outnumber people named Gary. Somewhere in the crowd, someone probably said, “We already have the beach, now we have the boys. Complete set.”

So yeah, on 13 January, Australia showed it can do extreme heat, floating roads, and imported harmonies—all before dinner.

Loading...

Wombats, Fishnadoes & Crumbling Dames: 12 January in Oz

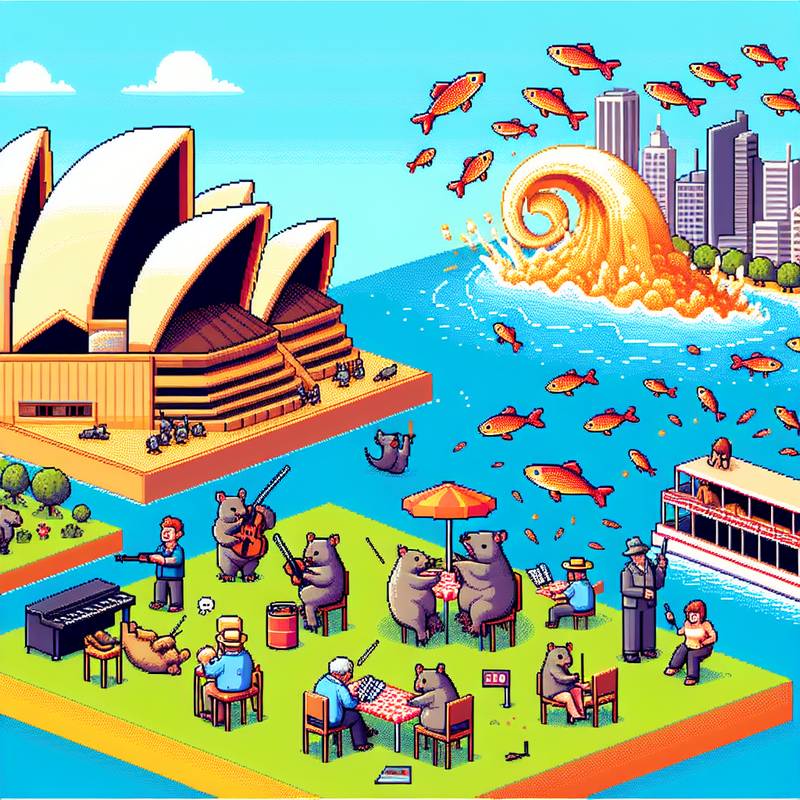

On this day (12 January), we find ourselves knee-deep in Aussie oddity! Back in 1973, the Sydney Opera House was still a few months from opening, but that didn’t stop a group of local wombats from trying to “rehearse” in the orchestra pit. One was caught nibbling on a violin. Maybe he fancied a bit of Bach for breakfast?

On this day (12 January), we find ourselves knee-deep in Aussie oddity! Back in 1973, the Sydney Opera House was still a few months from opening, but that didn’t stop a group of local wombats from trying to “rehearse” in the orchestra pit. One was caught nibbling on a violin. Maybe he fancied a bit of Bach for breakfast?Meanwhile, in 2004, Melbourne experienced what meteorologists described as a “fishnado” – a freak weather event that reportedly dropped dozens of small fish over a suburban garden. Locals took it as a sign to start a seafood BBQ. When life gives you airborne mullet, get the barbie going!

And who could forget the great sand sculpture collapse of 2010 in Surfers Paradise? A 10-foot depiction of Dame Edna crumbled just minutes before judging. A rival sculptor was seen walking away suspiciously with a suspiciously pointy stick. Coincidence? Or just a gritty feud?

So you see, Australia isn’t just home to curious creatures – even the weather and art get in on the act.

Loading...

Gold Rush Fever Dream, 1851–1900

In the dust and glare of 1851, men in tattered coats stumbled into Victoria’s goldfields with wild eyes and shovels, sleepwalking into fever. The land pulsed with promise—quartz veins bleeding wealth, rivers giving up secrets. Towns swelled grotesquely overnight: tents ashimmer, opium smoke drifting between punch-ups and German concertinas. Some struck it rich. Most struck mud. Melbourne exploded, swaggering into metropolitan adolescence on veins of bullion.

In the dust and glare of 1851, men in tattered coats stumbled into Victoria’s goldfields with wild eyes and shovels, sleepwalking into fever. The land pulsed with promise—quartz veins bleeding wealth, rivers giving up secrets. Towns swelled grotesquely overnight: tents ashimmer, opium smoke drifting between punch-ups and German concertinas. Some struck it rich. Most struck mud. Melbourne exploded, swaggering into metropolitan adolescence on veins of bullion. By the '60s, the gold was mostly gone or too deep, but the fever lingered. Railroads. Marble banks. An opera house rising like a dare. The gold didn't just build cities—it rewired the continent’s nervous system, turned bush tracks into trade routes, made miners dream in English, Cantonese, Gaelic.

And under the surface—deep, seismic shifts. Convicts started calling themselves free men. Australia started calling itself something more than a penal afterthought. Something raw, hungry, and momentarily golden. By the time the century closed, the gold had faded into myth, but the myth never left.

Loading...

Echoes Between the Coast and the Core

The sandstone memories of Sydney—its colonial bones and undying opera hum—stand in spectral contrast to the red breath of Alice Springs, where time is not measured in clocks, but in cracked earth and ochre dreams. Sydney, with its glass spires and toast-rack streets, clings to the edge of a sea that has forgotten the names of its convicts. It sips lattes atop ancient Aboriginal middens paved over with promises of modernity.

The sandstone memories of Sydney—its colonial bones and undying opera hum—stand in spectral contrast to the red breath of Alice Springs, where time is not measured in clocks, but in cracked earth and ochre dreams. Sydney, with its glass spires and toast-rack streets, clings to the edge of a sea that has forgotten the names of its convicts. It sips lattes atop ancient Aboriginal middens paved over with promises of modernity.But Alice Springs lies in the continent’s heart like a heartbeat beneath the dust, where stories are told not by buildings but by rocks older than language. The MacDonnell Ranges unwrap themselves like a revelation, each ripple a verse in a geologic psalm. Where Sydney looks out, Alice looks in—aboriginal songlines threading space and story, untranslatable to steel.

Culture in Sydney is curated; culture in Alice grows wild like spinifex, thorny and beautiful. One frames its past in museums; the other wears it as skin, as shadow, as breath.

Loading...

Australia: Where 9 January Is Just Built Different

On this day (9 January), Australia proved yet again that it's not just a country—it’s a whole vibe.Back in 1790, Captain Arthur Phillip got speared by an Indigenous man and survived. Now, being speared is bad, but what’s wilder is that Phillip didn’t retaliate with violence. Instead, he reportedly said, “Don’t worry, he probably had a reason.” That’s not just grace under pressure—that’s next-level Australian chill. I step on a Lego and declare war.

Then in 2007, the mercury hit 41.5°C in Sydney. That’s not summer—that’s oven settings. At that point, your sunscreen is just seasoning. Australians didn’t cancel plans—they just threw shrimp on the sidewalk barbecue and called it a day.

And speaking of survival, on 9 January 2020, wombats were spotted sharing their burrows with other animals during bushfires. Wombats, mind you—those glorified furry tanks. They became accidental Airbnb hosts in a crisis. Even the wildlife in Australia knows how to look out for each other. That’s not weird—that’s wonderful. It’s like a Disney movie set in Mad Max.

Loading...

From Rum to Rosemary Fries: The Aussie Pub Time Machine

Try to imagine colonial-era Australia: horse-drawn carts creaking across dust-thick roads, convicts hand-building sandstone pubs where you could trade a sheep for four beers and a fight to the death over who saw a platypus once. The 'pub' was your town hall, church, and dentist if someone had pliers and a strong left hook.Fast forward to today, and your average Aussie pub looks like it mated with a nightclub and a gluten-free bakery. There's locally-sourced squid ink aioli, a wine list curated by a man named Tristan, and trivia night hosted by someone with a ring light. You order everything on an app while your server sprints past on rollerblades delivering artisanal rosemary fries.

But buried under the microbrews and LED signage, there’s still that stubborn pulse of Aussie camaraderie. It's just wearing better shoes and probably has a loyalty card. Customs evolve. The spirit? Still cracking a beer with a stranger and calling them “mate” before you even know their name.

Loading...

Bushlollies and the Iron Tongue of Australia

In the swelter of the Outback, where even the flies seem to conspire, the word bushlollies once rolled on dry tongues. Not sweets, but dried animal droppings, handed a bitter name by desperate wit. It’s a term birthed not from cruelty but endurance, a wink against the sunburnt cruelty of the land.

In the swelter of the Outback, where even the flies seem to conspire, the word bushlollies once rolled on dry tongues. Not sweets, but dried animal droppings, handed a bitter name by desperate wit. It’s a term birthed not from cruelty but endurance, a wink against the sunburnt cruelty of the land. In that, there’s the essence of an older Australia—a place where humor was forged like iron, sharp and blackened by heat. To call dung a lolly is to laugh at scarcity, to find language in survival. The culture didn’t merely live in hardship; it christened it with its own wild tongue.

Words like bushlollies are vanishing, fading into dust tracks and wind. But they whisper of a time when language was a blade, not polished silver—rough, regional, and wielded to carve dignity from desolation. In the lexicon of hard lives, such words are both memorial and monument.

Loading...

The Spruiker’s Tongue

There is a word once tucked into the pouches of bushmen and shearers—spruiker. It refers to one who stands before the crowd, declaiming the virtues of wares with theatrical flourish. Not quite a salesman, yet not removed from the art of persuasion; the spruiker is a bard of the marketplace, echoing the outback’s peculiar marriage of spectacle and pragmatism.

There is a word once tucked into the pouches of bushmen and shearers—spruiker. It refers to one who stands before the crowd, declaiming the virtues of wares with theatrical flourish. Not quite a salesman, yet not removed from the art of persuasion; the spruiker is a bard of the marketplace, echoing the outback’s peculiar marriage of spectacle and pragmatism.To spruik is to believe that words can dress a thing up better than silk. It requires not cunning alone, but a kind of antipodean audacity—an ease with laughter, a respect for larrikinism, and above all, a tacit agreement with the listener that this is part performance, part negotiation.

Australia, vast and often wordless, gives birth to such terms that suggest the culture is not solemnly silent, but wry and watchful. The spruiker stands on the kerb like an impromptu philosopher, reminding us that even in a sunburnt land, the tongue remains fertile.

Loading...

The Echo of Yabber

A word once alive in the red dust of Australia has gone quiet now—yabber, meaning to talk, often too much, often too loudly. It came from the Indigenous word yaba, meaning speech or talk, and passed into colonial English not with violence but with a kind of amused acceptance. There is something deeply humane in adopting a word that captures, not grandeur or conquest, but the simple, unquenchable need to speak.

A word once alive in the red dust of Australia has gone quiet now—yabber, meaning to talk, often too much, often too loudly. It came from the Indigenous word yaba, meaning speech or talk, and passed into colonial English not with violence but with a kind of amused acceptance. There is something deeply humane in adopting a word that captures, not grandeur or conquest, but the simple, unquenchable need to speak.To yabber is not to orate or to sermonise. It is the talk of windmills creaking and billy cans boiling, the talk of long afternoons with no clocks, of mateship and memory. It is at once unpretentious and essential. That such a word might vanish says less about language and more about a culture’s shifting posture toward its own informality—the quiet erosion of the colloquial in favour of the global.

Still, every old word buried in time is a fossil of the mind. And like all things fossilised, it speaks—when we bother to listen.

Loading...

Australia’s 3rd of January: Nature’s Freakshow on a Barbecue

On this day 3 January (03/01), Australia, the land where even the pigeons look like they’ve done time, saw a string of strange wonders. In 1962, an Extinct Queensland Lungfish was found alive and well in a muddy creek, instantly making every scientist feel like they'd been mugged by evolution. Only in Australia can a “scientific impossibility” climb out of a puddle and go, “You missed me, idiots!”

On this day 3 January (03/01), Australia, the land where even the pigeons look like they’ve done time, saw a string of strange wonders. In 1962, an Extinct Queensland Lungfish was found alive and well in a muddy creek, instantly making every scientist feel like they'd been mugged by evolution. Only in Australia can a “scientific impossibility” climb out of a puddle and go, “You missed me, idiots!”And in 1984, the temperature in Marble Bar hit 45.2°C. That’s not weather—that’s the inside of a gas oven. You could fry an egg on the street and cook the chef while you were at it.

Meanwhile, in 1988, a man reportedly rode a lawnmower from Brisbane to Darwin. Why? Probably because his fridge was already full of empty beers and regret. Nothing says “personal growth” like navigating the Outback at 9 kph with sunstroke and a mullet.

Australia on 3 January isn't just a country—it’s a David Attenborough documentary narrated by Hunter S. Thompson while being set on fire.

Loading...

2 January: Lightning, Emus, and Existential Pavement

On this day 2 January (in the 2 January), Australia continued doing what it does best: behaving as if the laws of physics, probability, and common sense had misread the map and wandered off somewhere safer.

On this day 2 January (in the 2 January), Australia continued doing what it does best: behaving as if the laws of physics, probability, and common sense had misread the map and wandered off somewhere safer.In 1972, the Sydney Opera House, still unfinished and looking like an alien spaceship mid-transformation, was struck by lightning, which is precisely the sort of thing that happens when you build a musical venue shaped like a stack of divine taco shells. Miraculously, it endured the celestial critique, and concerts resumed with slightly more frequency.

Back in 1954, an emu named Trevor became briefly famous for escaping from the Adelaide Zoo and leading five zookeepers, two police officers, and a confused jazz band on a chase through the city before calmly re-entering his enclosure. Nobody ever determined whether Trevor actually escaped or just went for a strut.

And finally, in 1965, temperatures in Marble Bar reached 49.2°C, causing sidewalks to develop existential doubt and thermometers to unionise. Locals remained unfazed, claiming it was 'a bit toasty.

Loading...

Whispers of South West Rocks

The rocks under Horseshoe Bay in South West Rocks breathe. At least, that’s what it feels like if you’re standing on the point during a windless dusk, when the waves disappear into themselves instead of crashing. Locals won’t tell you that—it’s not a secret, just irrelevant until you’ve felt it. The rocks aren’t alive, not technically, but the tide flows beneath them into hidden pockets, making the bay sigh like a living organism.

The rocks under Horseshoe Bay in South West Rocks breathe. At least, that’s what it feels like if you’re standing on the point during a windless dusk, when the waves disappear into themselves instead of crashing. Locals won’t tell you that—it’s not a secret, just irrelevant until you’ve felt it. The rocks aren’t alive, not technically, but the tide flows beneath them into hidden pockets, making the bay sigh like a living organism. Teenagers from the area use those tidal gaps as confessionals—whisper your adolescent heartbreaks into the stone, and the ocean carries them away. It’s not written on maps or signs, just passed down from someone older, shirtless with sun-bleached hair, fuelled by boredom and meat pies.

Visitors chase the obvious—sun, surf, and selfies near Trial Bay Gaol. Locals know the true ritual: swim out just after sunrise, float with your ears underwater, and hear the rocks speak back. They echo your thoughts—filtered, somehow kinder. Like they know how it ends. Like they’ve seen everything before.

Loading...

Prawns, Proposals, and Roo Suits

On this day (31 December), a man in Darwin proposed to his girlfriend with a ring hidden inside a mango. She bit into it and broke a molar, which is not the worst thing that’s happened to anyone in the Northern Territory on New Year's Eve, but arguably the most tropical.

On this day (31 December), a man in Darwin proposed to his girlfriend with a ring hidden inside a mango. She bit into it and broke a molar, which is not the worst thing that’s happened to anyone in the Northern Territory on New Year's Eve, but arguably the most tropical.That same day, across the country, someone dressed as a kangaroo performed interpretive dance on Bondi Beach, convincing no fewer than seven tourists that “this is how Australians celebrate the new year.” He had a speaker taped to his chest playing INXS and no one thought to question him, because frankly, who’s going to interrogate a hopping man in Lycra when it’s 37 degrees and everyone’s been drinking since 10 a.m.?

There’s something about Australia on the last day of the year that turns everyone slightly feral in the best possible way. It’s the only place I’ve seen a countdown shouted over a plate of barbecued prawns, followed by group cannonballs into a stranger’s above-ground pool.

And somehow, that feels right.

Loading...

Paronella Park: Mossy Romance in the Rainforest

There’s a place up north called Paronella Park, and it’s like if Gaudí had a tiki dream about a rainforest and then built it from romance and moss. José Paronella, a Spanish sugarcane baron with a heart the size of Neptune, built a castle here in the 1930s for his beloved Marguerita. Now it crumbles gently under the weight of vines and starlight, a ruin wrapped in moon-drenched drama.

There’s a place up north called Paronella Park, and it’s like if Gaudí had a tiki dream about a rainforest and then built it from romance and moss. José Paronella, a Spanish sugarcane baron with a heart the size of Neptune, built a castle here in the 1930s for his beloved Marguerita. Now it crumbles gently under the weight of vines and starlight, a ruin wrapped in moon-drenched drama.Waterfalls hum lullabies, while fish loiter like tiny philosophers in the ponds. There’s a cinema for ghosts (seriously), and staircases that seem to spiral into poetry. Lava rock walls erupt from the greenery like gothic cupcakes. It's not Instagrammable – it’s instagrandmotherable, ancient and soulful, echoing with the laughter of tropical fairies in gumboots.

People flock to the big-name reefs and rocks, but Paronella is a whisper, not a shout. A sugar-dream fading beautifully in the jungle's pocket. Go there and feel time unbutton its waistcoat.

Loading...

Between Mist and Fire

The Blue Mountains rise like a memory — cool, veiled in eucalyptus breath, with valleys that hold silence like an old wound. There’s a hush there, a reverence, as though the land remembers grief and speaks it in mist and shadow. Men don’t shout in the Blue Mountains; they linger, slow-footed, as if afraid their voices might wake something buried.

The Blue Mountains rise like a memory — cool, veiled in eucalyptus breath, with valleys that hold silence like an old wound. There’s a hush there, a reverence, as though the land remembers grief and speaks it in mist and shadow. Men don’t shout in the Blue Mountains; they linger, slow-footed, as if afraid their voices might wake something buried.But travel north to Darwin, where sweat dances down your spine before the sun lifts its chin. Life in Darwin is a fever dream — bold, blunt, and cracked from the sun. It's a place where history hums under your feet, hot with cyclones and scars. Folks walk with a swagger there, laughter loud, survival louder.

These two places don’t just differ — they resist one another. The Mountains whisper, 'Wait. Darwin shouts, 'Now!' One invites introspection through cool exile; the other demands participation in its defiant blaze. And somewhere between them — in the stillness or the storm — lies a truth about Australia: beauty forged in contrast, and home found in the tension.

Loading...

Quakes, Cars, and Cricket: 27 December Down Under

On this day (27 December), the Australian calendar coughs up more than just sunburn and leftover pavlova. In 1945, the nation shrugged on its first Holden prototype like an awkward but promising teenager trying on dad’s suit. It was an awkward metallic foreshadowing of suburban dreams—plonked together with the hope of motoring autonomy and a hint of Detroit envy.

On this day (27 December), the Australian calendar coughs up more than just sunburn and leftover pavlova. In 1945, the nation shrugged on its first Holden prototype like an awkward but promising teenager trying on dad’s suit. It was an awkward metallic foreshadowing of suburban dreams—plonked together with the hope of motoring autonomy and a hint of Detroit envy.Fast-forward to 1989, when Newcastle's teeth chattered under a 5.6 magnitude earthquake—the strongest in Australia’s recorded history. Not a land known for tectonic drama, and yet buildings cracked like stale Anzac biscuits. Nature, it seemed, wanted a word.

And then there’s the annual Boxing Day Test hangover. December 27 is when the cricket becomes chess: strategy replacing spectacle, sunstroke replacing narrative arcs. Somewhere, a child in Perth discovers Shane Warne on replay and believes, quite reasonably, that spin is sorcery.

Australia, on this day, becomes a theatre of quiet spectacle—where the improbable hums just beneath the surface, dressed up in sunscreen and silence.

Loading...

auslistings.org (c)2009 - 2026